Monte Carlo Simulation#

In molecular dynamics, we model chemical systems by numerically integrating equations of motion to generate trajectories through time. Starting with atomic positions and velocities at time \(t\), we calculate the forces, update positions and velocities, and repeat this process to simulate molecular motion. In addition to providing direct insight into the microscopic dynamics of our system, molecular dynamics also allows the calculation of thermodynamic averages over functions of all positions and/or momenta of particles during the simulation. However, there are several situations where molecular dynamics cannot be used to calculate thermodynamic averages:

We might not be able to calculate the forces \(F(r)\) required for MD. This could be because force evaluation is computationally expensive, or because the forces are not well-defined for our system. Either way, we are now unable to solve the equations of motion for our system.

The timescale of important transitions might be much longer than we can practically simulate. For example, protein folding or chemical reactions with high activation barriers can take milliseconds or longer, while MD timesteps are typically femtoseconds. In these cases, we are unable to fully sample the configurational space of our system, and any average values we calculate will not be correct thermodynamic averages.

Our system might have a discrete, rather than continuous, configuration space. For example, a lattice model where molecules occupy specific sites, or magnetic systems where spins point only up or down. How can we sample different configurations to compute thermodynamic averages?

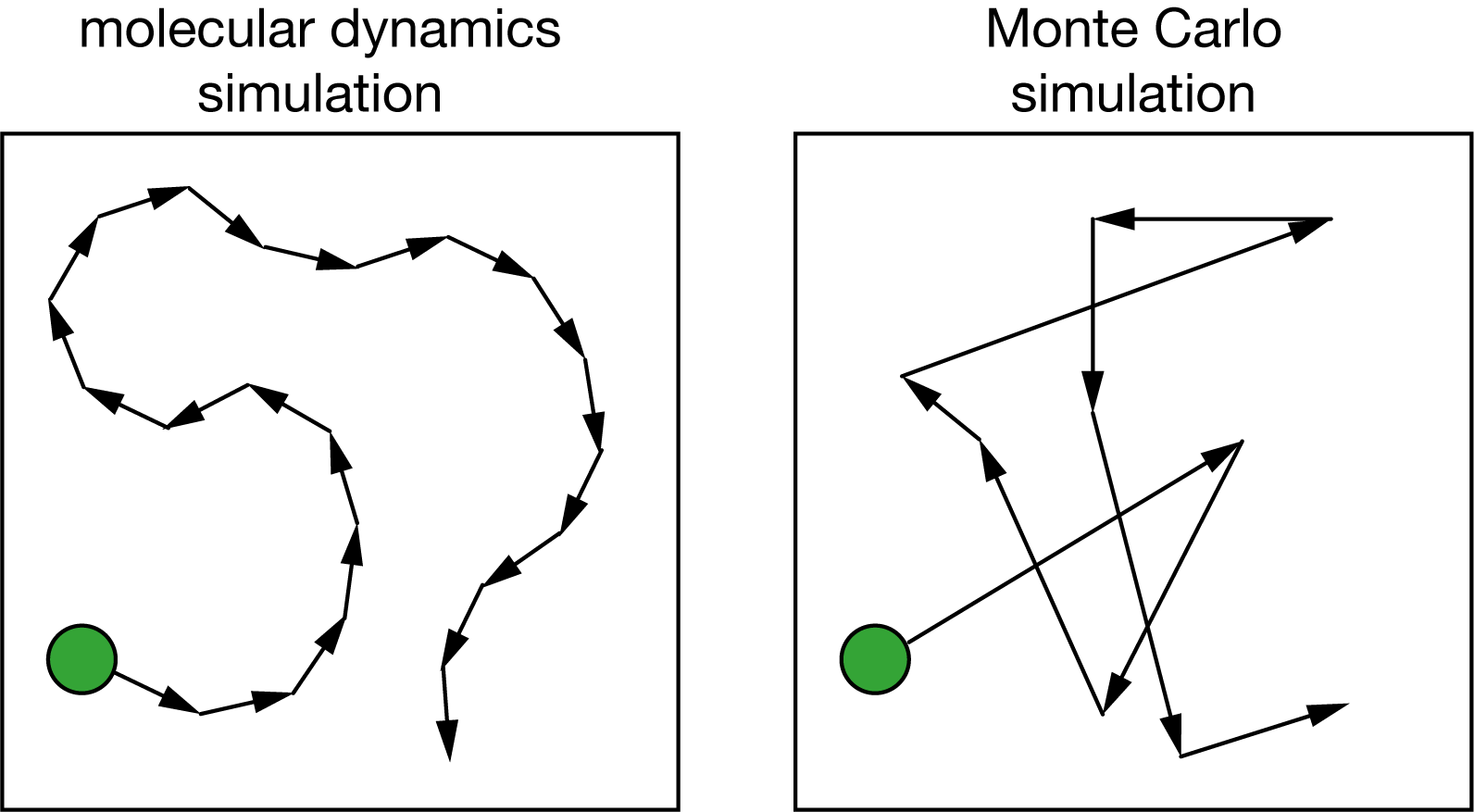

Monte Carlo simulation offers an alternative approach. Rather than following the detailed dynamics of molecular motion, Monte Carlo methods use random sampling to explore configuration space and calculate equilibrium properties. This can overcome many of the limitations of molecular dynamics, at the cost of losing information about true dynamical behavior.

Fig. 10 In molecular dynamics we integrate equations of motion to generate a continuous trajectory through configuration space. In Monte Carlo we use random numbers to sample configuration space discontinuously.#