Potential Energy Surfaces#

A common concept in theoretical and computational chemistry is that of a potential energy surface.

The potential energy surface for a molecular describes the relationship between the molecular geometry, i.e. the relative positions of the component atoms, and the molecular energy.

Potential energy surface for a diatomic molecule#

In general, the potential energy surface for a system of atoms is a complex multidimensional function. For a system containing \(N\) atoms the relative positions of these atoms is described by \((3N-6)\) degrees of freedom (this becomes \((3N-5)\) in the case of a linear molecule). This makes it difficult to visualise full potential energy surfaces in all but the simplest cases, and instead we often consider only those degrees of freedom that are chemically important—for example, how the energy of a system varies as we move along the reaction coordinate.

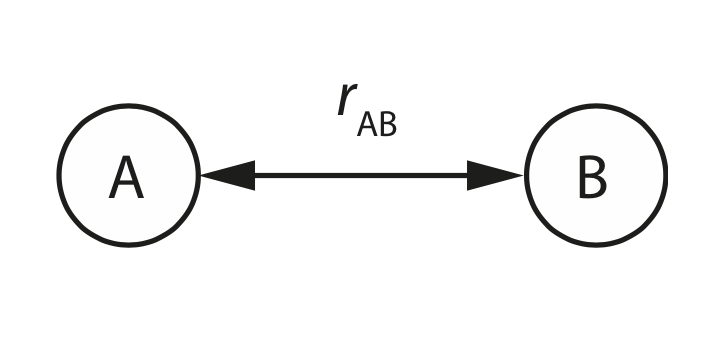

Here, we will start with an example potential energy surface for a pair of atoms.

For a pair of atoms \(A\) and \(B\), we have only one degree of freedom: the interatomic separation \(r_\mathrm{AB}\).

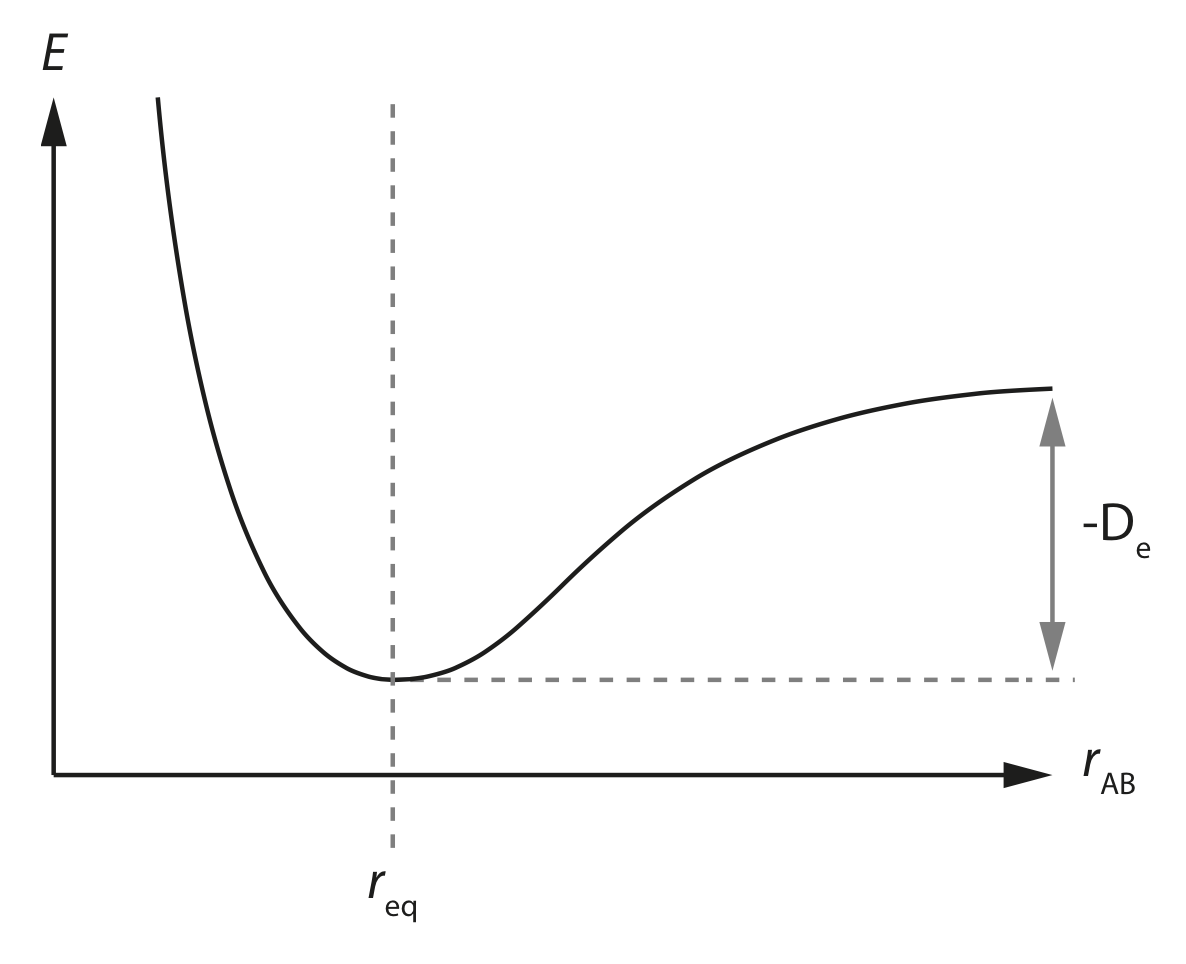

If these atoms form a diatomic molecule, then we might expect a potential energy surface that looks something like the figure below:

Here the \(x\) axis is our degree of freedom; the interatomic separation \(r_{AB}\), and the \(y\) axis is the energy of our molecule.

This potential energy surface has a single minimum energy at \(r_\mathrm{eq}\), which is the equilibrium separation of the two atoms \(A\) and \(B\).

If we move \(A\) and \(B\) closer together then the energy continually increases, due to the increasing repulsion between our two atoms. This repulsive interaction at short distances is due to Pauli repulsion , and is due to the Pauli exclusion principle.

If we move \(A\) and \(B\) further apart then the energy again increases, but only up to a point. At sufficiently large interatomic separations the energy plateaus. This corresponds to “breaking” the bond between atoms \(A\) and \(B\).

The difference in potential energy between the minimum energy at the equilibrium distance \(r_\mathrm{eq}\) and the plateau at large interatomic separations is given by \(-D_\mathrm{e}\) which is the depth of the potential energy well for the bond \(A\)—\(B\).

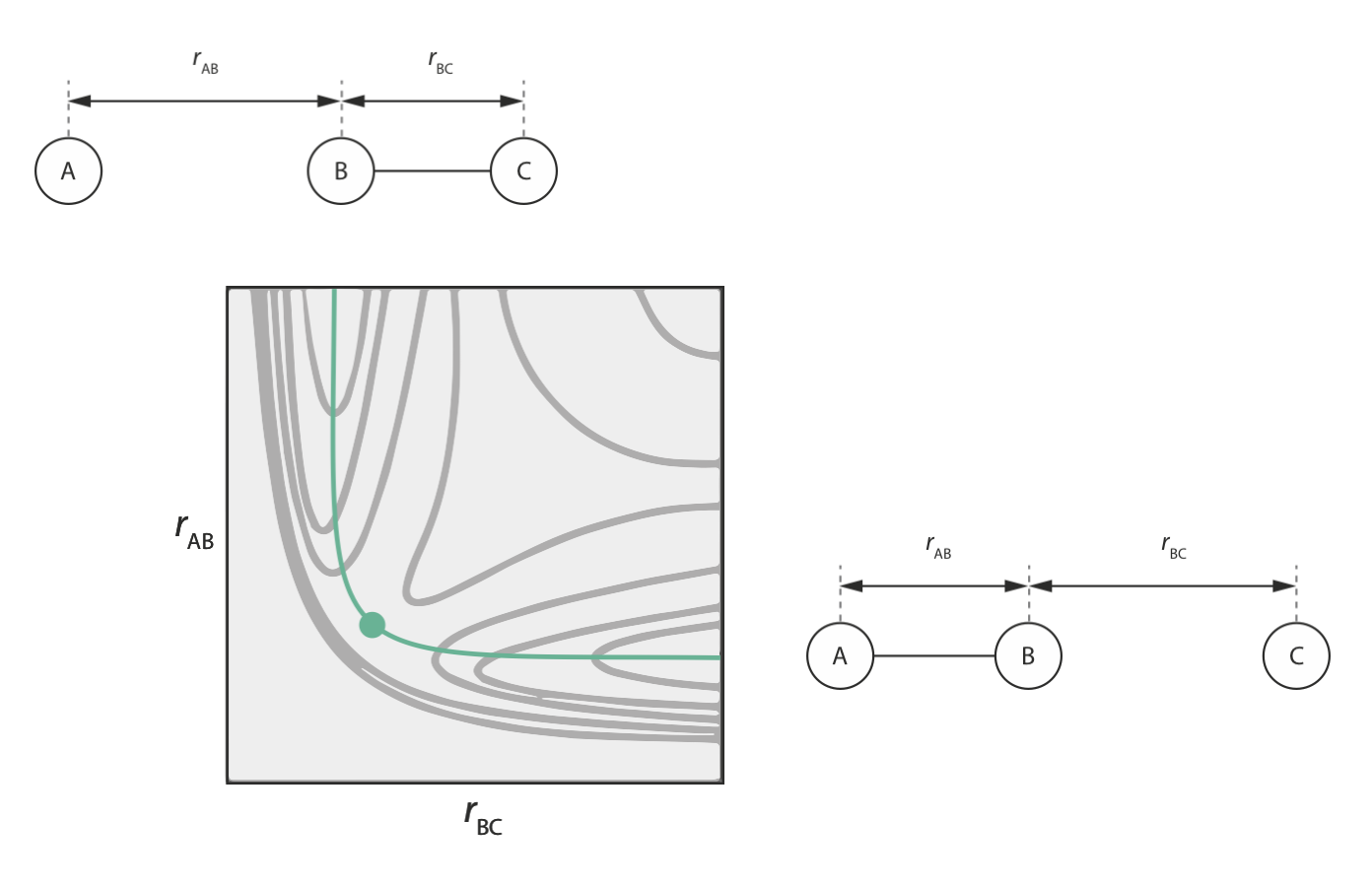

Potential energy surface for a system of 3 atoms.#

Collinear case#

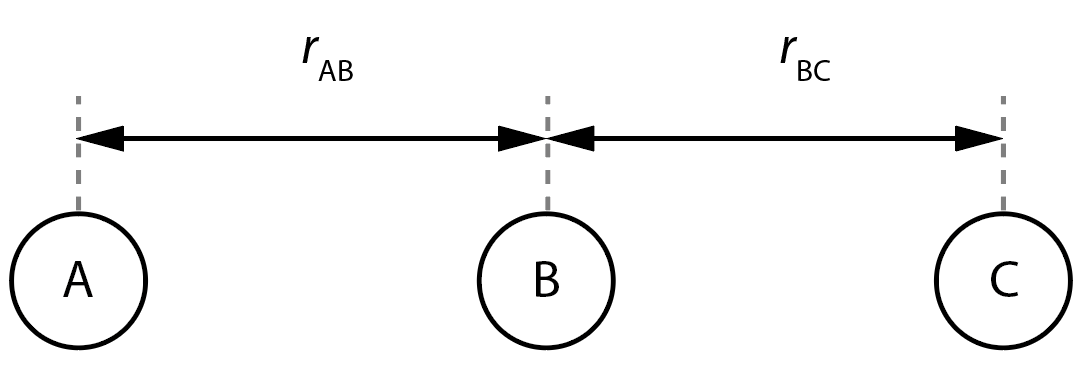

For a system of three atoms we can have two cases. If the atoms are collinear then we have two degrees of freedom.

In the example above, the relative positions of the atoms A, B, and C are given by the interatomic distances \(r_\mathrm{AB}\) and \(r_\mathrm{BC}\).

The figure below shows the potential energy surface for a reaction A + BC → AB + C via a collinear transition state.

In our initial configuration, B and C are bonded, so \(r_\mathrm{BC}\) is small; while A and B are well separated, so \(r_\mathrm{AB}\) is large.

In the final configuration, A and B are bonded, so \(r_\mathrm{AB}\) is small; while B and C are well separated, so \(r_\mathrm{BC}\) is large.

Note that the two-dimensional potential energy surface for this reaction allows us to specify the minimum energy pathway from the initial configuration (A + BC) to the final configuration (AB + C) (shown in green above). This minimum energy pathway represents the reaction coordinate for this reaction. The maximum energy point along this pathway is the transition state along our reaction coordinate.

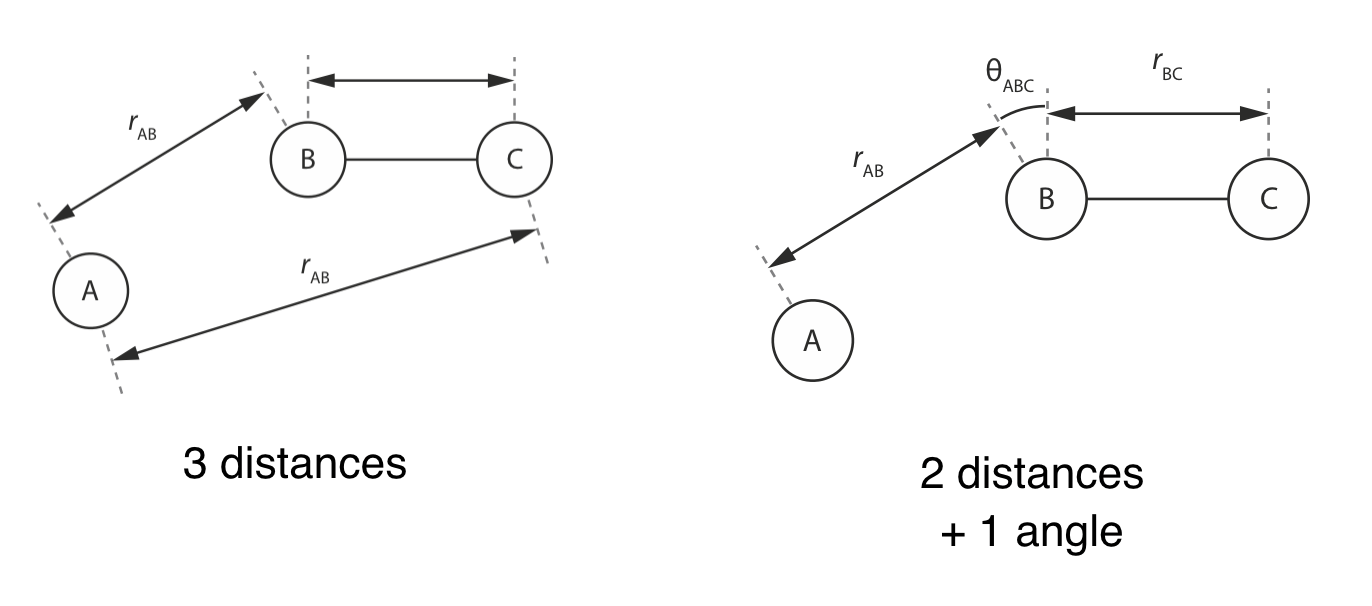

Non-collinear case#

For a non-collinear 3-atom system things are more complicated: we now have three degrees of freedom, making the potential energy surface four dimensional (3 geometric degrees of freedom, plus the energy).

Note that the degrees of freedom we choose to describe our system need not be interatomic distances. Below we show two examples of parameter sets that describe the same three atom system. In the first example the atomic geometry is described by three interatomic distances, \(r_\mathrm{AB}\), \(r_\mathrm{BC}\), and \(r_\mathrm{AC}\). In the second example we instead describe the atomic geometry as a function of two interatomic distances \(r_\mathrm{AB}\) and \(r_\mathrm{BC}\) and a three-body angle \(\theta_\mathrm{ABC}\).

As this example shows, we often have some flexibility in our choice of coordinate system used to describe our potential energy surface: the only requirement being that the coordinate system we choose defines an orthogonal basis (i.e. each degree of freedom can be varied independently of the others).

Potential energy surfaces for \(N>3\)#

For systems of atoms with \(N>3\) the number of degrees of freedom quickly becomes too large to allow us to describe the full potential energy surface graphically.

In many cases, however, we can focus on a relevant subset of the full set of degrees of freedom; for example considering the potential energy profile along a reaction coordinate, or focussing on one particularly important degree of freedom.

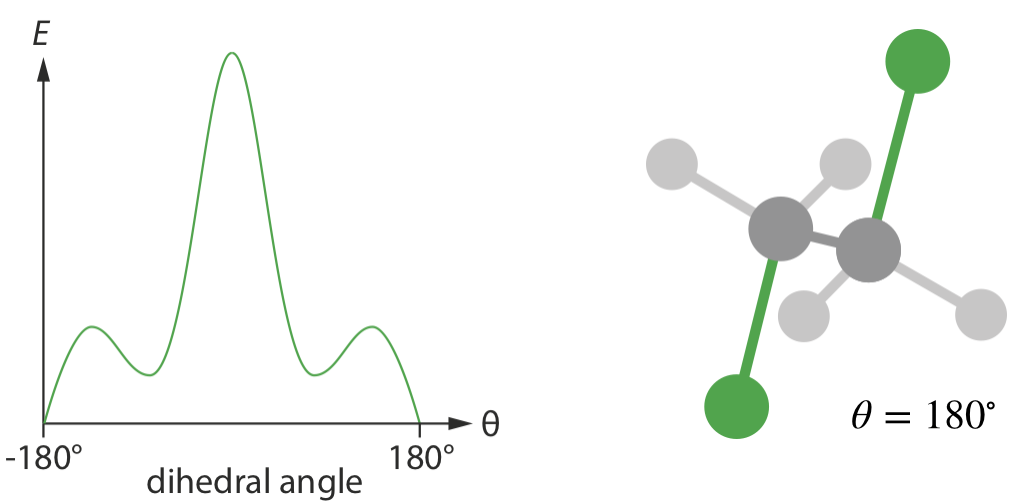

As an example, consider the potential energy of dichloroethane, C22H4Cl2 as a function of the Cl—C—C—Cl torsion angle \(\theta\).

Because we are considering only one degree of freedom, we can plot this potential energy surface in two dimensions.

Despite projecting a single degree of freedom out of the full 12-dimensional potential energy surface, this gives us a lot of chemically relevant information about the molecule:

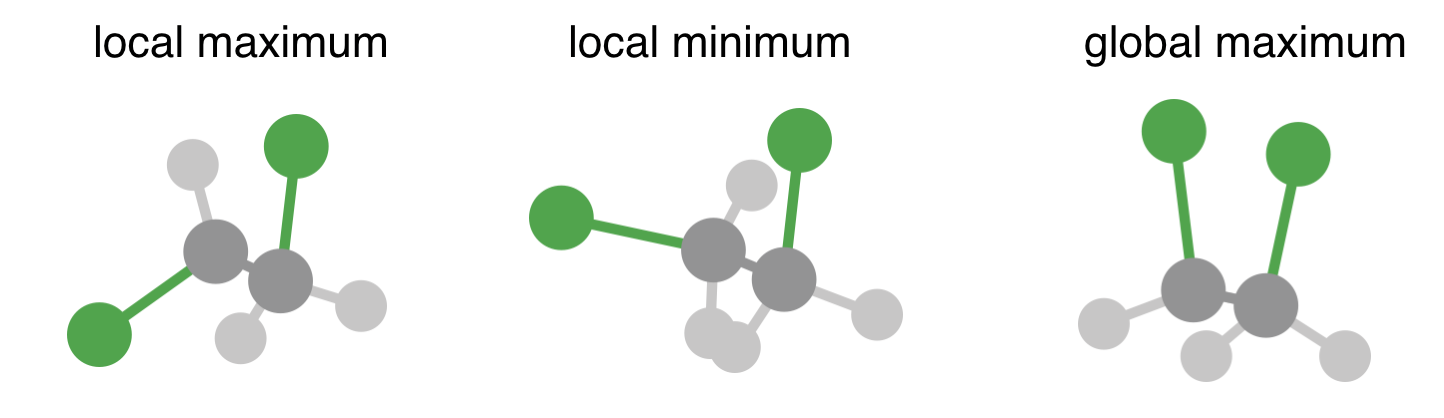

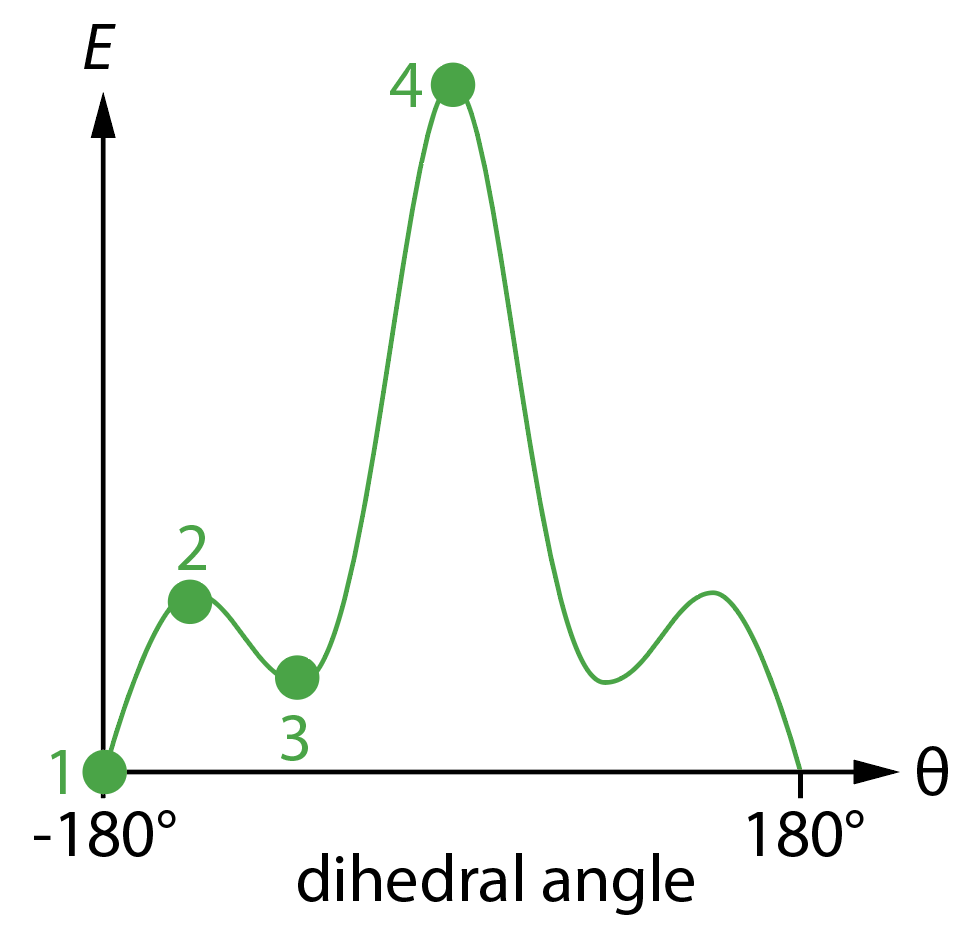

1 is the lowest energy configuration, when \(\theta = 180^\circ\), corresponding to the two C–Cl bond having opposite orientations, i.e. an anti-staggered conformation. This is the lowest energy point on the potential energy surface, called the global minimum.

2 is a local maximum on the potential energy surface. This corresponds to an eclipsed conformation, and gives us the energy required to bring each C–Cl bond coplanar with a C–H bond.

3 is a local minimum. Increasing or decreasing \(\theta\) causes the energy to increase, yet the energy is higher than at the global minimum. This corresponds to a staggered conformation where the angle between the two C–Cl bonds in \(\pm 60^\circ\). Note that there are two of these local minima that are equivalent by symmetry.

4 is the global maximum, i.e. the highest energy position on this potential energy surface. This corresponds to the eclipsed conformation with both C–Cl bonds coplanar.